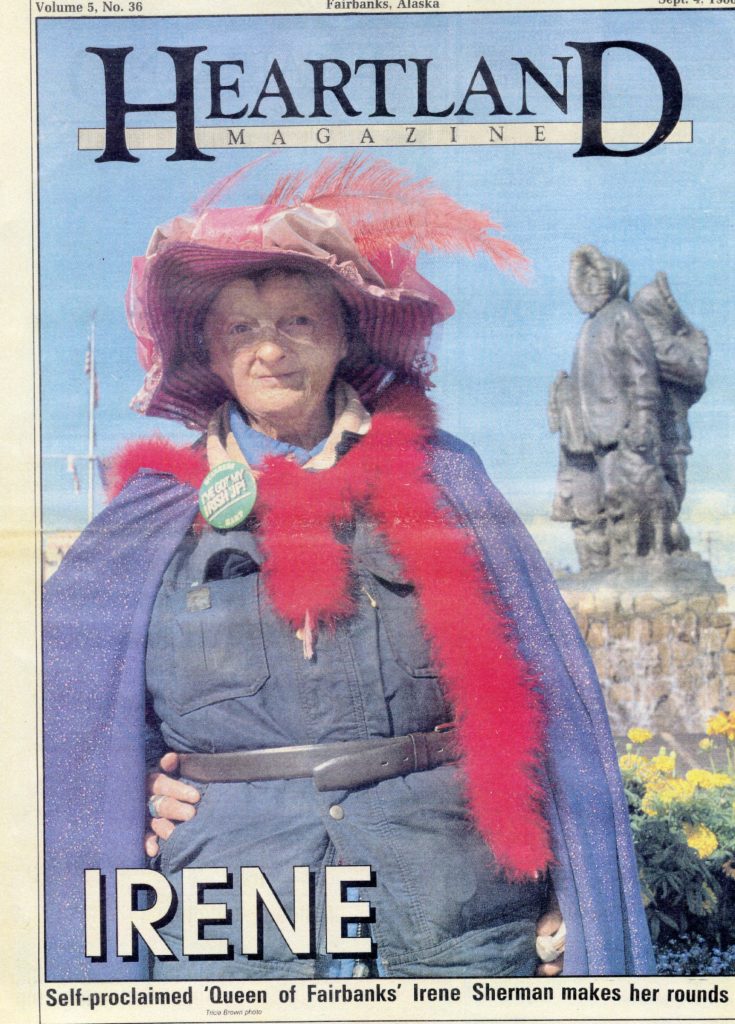

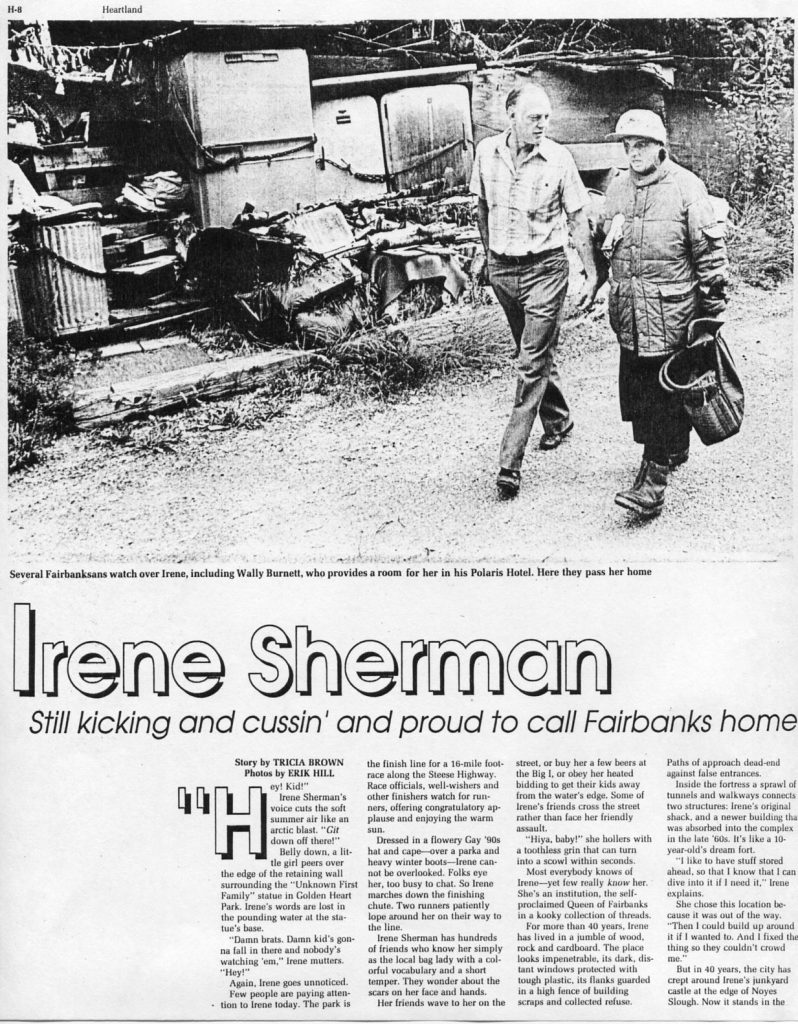

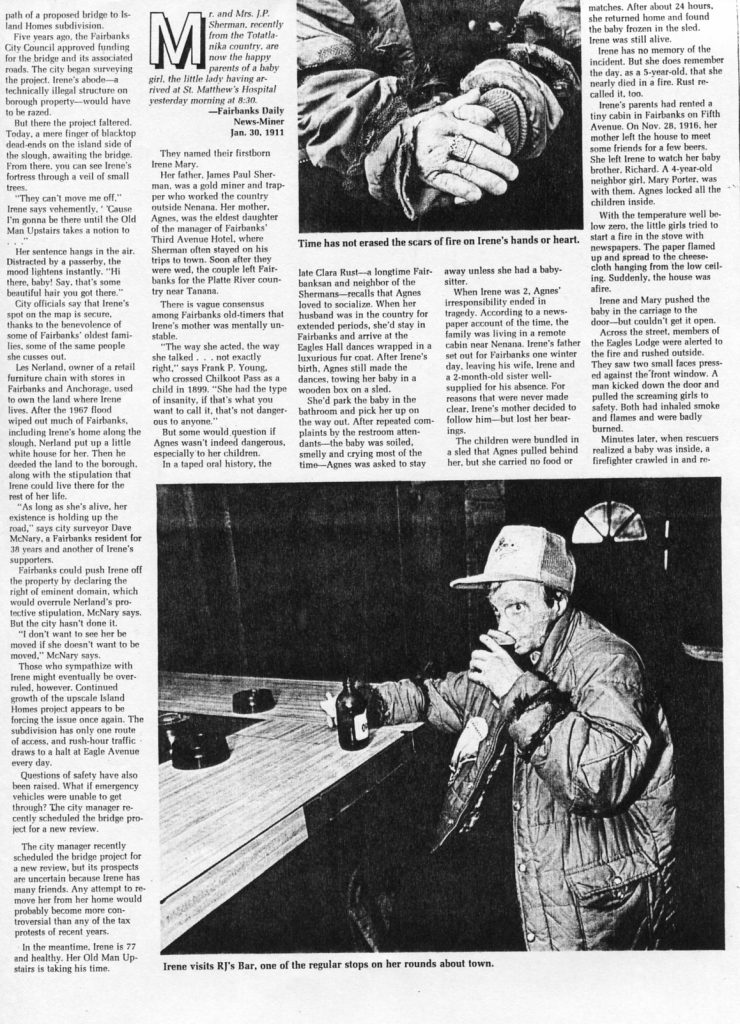

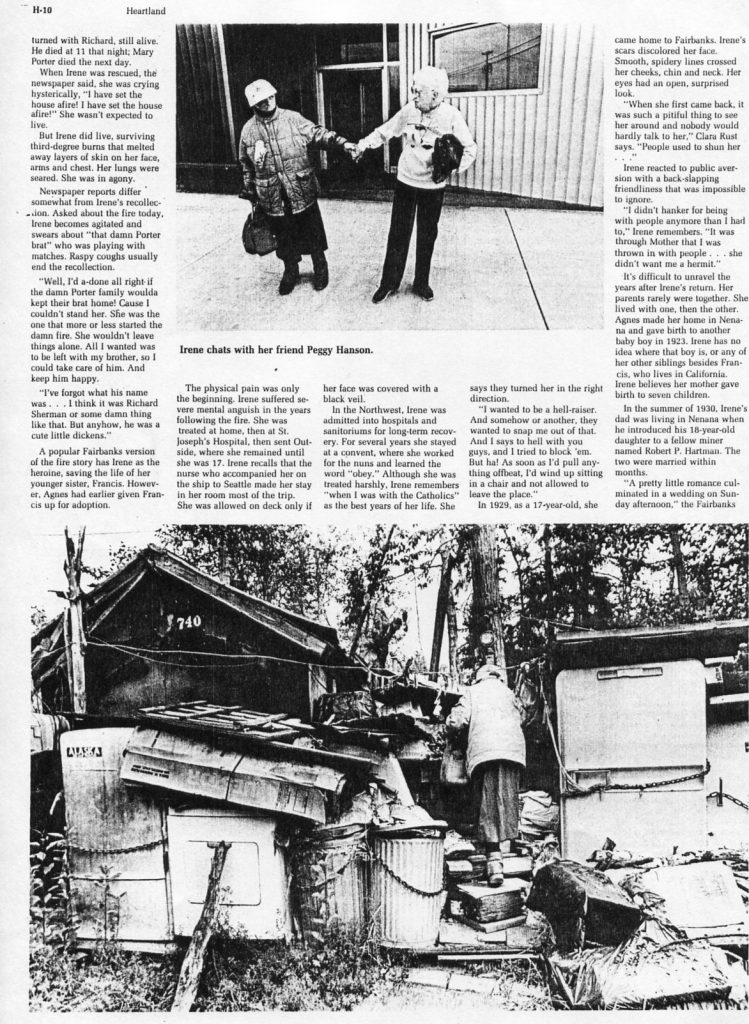

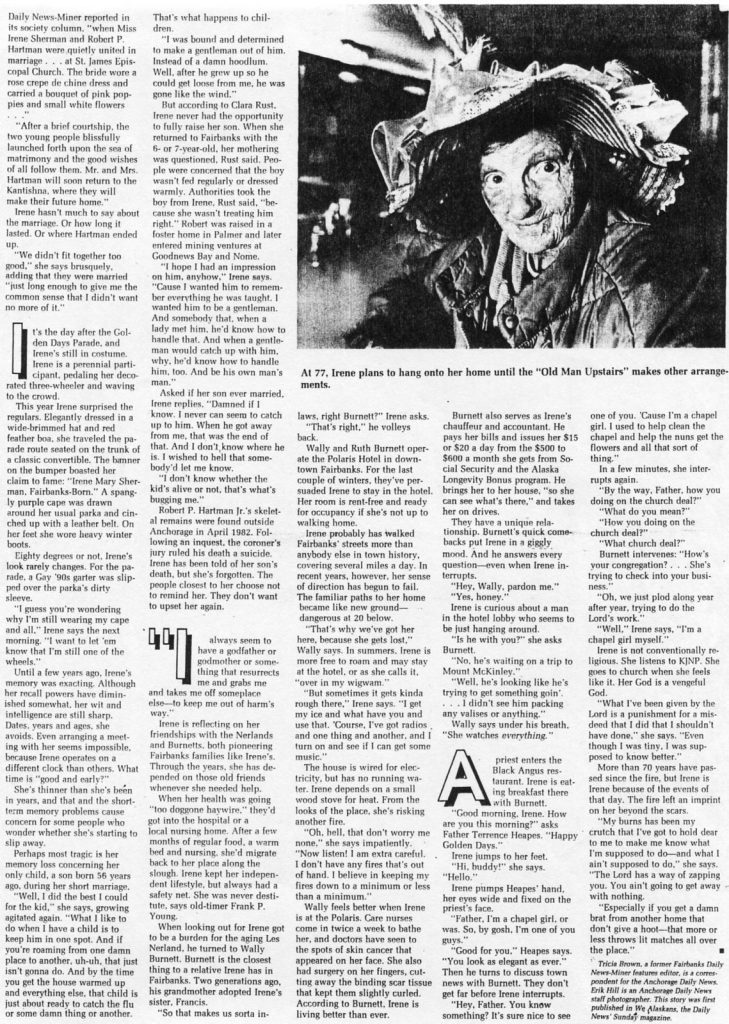

I got my start writing and editing feature stories for daily papers in Fairbanks and Anchorage. Over the years, I wrote dozens and dozens of stories about Alaskans, who they are and what they care about. I don’t think I could ever go back to a daily deadline, but there’s something about that newspaper byline that still thrills me. I wrote one of my favorite freelance stories in 1988, when I pitched the idea to study and write about Irene Sherman, a well-known “bag lady” with a badly scarred face and hands. She had been born and raised in Fairbanks, and her presence on the city streets was common, but few knew the true story of Irene’s tragic life. Many passed around their own colorful stories, and it was a challenge to find truth when interviewing a slightly off-kilter woman who lived in an old house barricaded by refrigerators, broken pallets, and an assortment of junk. Photographer Erik Hill brilliantly captured images of her everyday life. Here’s the story as it appeared in the Sunday magazine of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner:

Writing books involves this thing called “delayed gratification.” You grind out the best book you can write, revise endlessly, submit it to a publisher, and pray for a contract. All of which takes months, and sometimes a year or more. Then there are the steps of editing, designing, and manufacturing the book—again, months go by. Eventually, the pub date arrives and your “baby” is delivered.

While we were living in Oregon, I returned to some freelance newspapering in my spare time. For me, writing travel features is the best way to taste some instant gratification. It’s days or weeks instead of months and years. Here are some travel pieces that I wrote for The Oregonian, Portland’s daily newspaper.

GREENHORN GETS RIDE OF A LIFETIME ON ALASKA WILDERNESS TREK

© Sunday Oregonian, May 17, 2009

By Tricia Brown

Study a map of Alaska, and you won’t find a dot for Horsfeld. It lies inside Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, a 13.2-million-acre parcel that became America’s biggest national park in 1980. Located within the preserve area, Horsfeld is one of the rare places in Alaska where you can book a stay at a remote horse camp. I’d lived in Alaska for 21 years but never taken up this kind of adventure. When one of my best friends proclaimed a week in the Bush (on horseback!?) our next gal-pal rendezvous, I agreed. Maybe it was because I’d recently reached the windward side of fifty.

In the late 1890s and early 20th century, when gold fever was burning up the North, this valley near the Alaska-Canada border was indeed a “horse field,” ideal pastureland for horses peddled to stampeders. And the trails they followed during Alaska’s Chisana gold rush of 1913 are still in use today.

The historic camp—a clutch of wall tents and rustic cabins—is where Fairbanks residents Dick and Gretchen Petersen do business as Wrangell Outfitters, a private concession within the preserve. They spend each summer and fall leading guests into the Nutzotin Mountains, feeding them plentiful, healthy food, and seasoning their evenings with storytelling and music. The Petersens’ hired hands do everything from pouring coffee to shoeing horses to hefting chubby clients into the saddle. (Ahem.) Trail options and difficulty levels vary from family rides to extra-tough cross-country excursions.

At the end of season, the horses’ shoes come off and they’re turned loose for a winter in the wilds. Decades of rusting shoes are lined up in rows on the corral’s fence rails, like a horseshoe abacus. Each spring, the animals are rounded up and re-acclimated to shoes and saddle. How do they survive? I wonder. In January, there’s two feet of snow and mean low is –23; the mean high is –5. But clearly they manage, with only an occasional loss from a wolf kill.

A Wyoming native, Dick Petersen is a tough, hard-working guy who can expertly balance a pack animal’s load, track big game, or fry up a stringer of trout over campfire coals. His face is tanned and lined from years of outdoor labor, and he goes from grim to grin in a millisecond. Gretchen is born-and-bred Alaskan, friendly, efficient, and the picture of robust health, beautiful sans a drop of make-up. She is skilled at merging her Le Cordon Bleu culinary training with hearty backcountry cooking. The couple met as teenagers, then took different trails with other partners before their paths crossed again, culminating in marriage and this melding of their talents.

Wrangell Outfitters caters to small groups and ours numbered six, including author Pam Houston, famed for her award-winning book, Cowboys are My Weakness, among others. Houston’s work has been described as “bright and edgy,” and she rides as well as she writes. Soon I would discover that cowboys were my friends, and a sore butt was my weakness.

The Horsfeld cowboys were patient teachers with even the greenest greenhorn, such as I, who feared horses for their brutish mass and hooves and teeth and clever ways of ejecting riders. Horses had bettered me many times since childhood, so this big-girl camping trip was, for me, the path to mastering an irrational fear among friends.

Kris Capps, Sherry Simpson and I landed at Horsfeld in a four-seater plane after a low, winding flight from McCarthy over the rugged terrain of the Wrangell Mountains. Flying in, we’d photographed glaciers spilling down the mountainsides and broad, braided streams wending toward the Gulf of Alaska. Our pilot spotted a band of Dall sheep, white dots on the mountainside. This country grows them big, and trophy hunters consider the Wrangells an ultimate destination. In fact, each fall, Dick shifts from leading backpackers and shutterbugs to guiding big-game hunters.

From the airstrip to the Horsfeld camp was about a half-mile hike. There we found the main log cookhouse, a couple of tack cabins, corral, and a sprinkling of wall tents tucked in the trees. We learned that they cook with propane and wood, charge batteries with solar panels, and as for running water, well, it’s running right out there in Beaver Creek. I claimed a cozy wall tent for one, outfitted with a cot, a small woodstove, and a crude table adorned with wildflowers and a jug of drinking water.

The corral was adjacent to another historic log cabin, creaky but still at work as a tack room “shingled” with flattened metal fuel containers, the fading print still visible. Nearby, a dozen horses swished their tails at merciless mosquitoes and no-see-ums. Which horse will be mine? I wondered. On the flight, we’d imagined names like Widder-Maker and Satan’s Seed. That would be my luck.

On the morning of our first ride, I took a lesson on how to board a horse—or I guess it’s called Mounting. Getting on the saddle, anyway. Then how to hold the reins and make speed suggestions with my feet. Dick had assigned me to a horse that was neither Widder-Maker nor Satan’s Seed. His name was Igo. As is I go, I don’t go. Igo was an equine wind-up toy. As our party rode in single file, his pace seemed to slow, imperceptibly at first, but gradually we fell way back. Then he’d jolt with realization and trot to catch up. Hanging onto the saddle horn, I grunted “Mer-cy!” as my undercarriage slapped the saddle.

After a five-hour ride, I waddled to the wall-tent sauna at the edge of Beaver Creek. Some kind soul had fired up the woodstove and the bucket of river water on top was already deliciously hot. My knotty muscles melted.

When it was time to saddle up the next morning, Dick must have overheard me talking to my cowboy: “Would it be possible to put that saddle blanket on TOP instead of under?” Moments later, he handed me a thin seat cushion from the kitchen. I thought about putting him in my will.

A day later, after I’d dispatched three or four ibuprofen and a half tube of Ben-Gay, Dick put me on a Cadillac of a horse that powered over hills and valleys at one steady speed. No spontaneous trotting. At last I learned to relax in the saddle, and even look around.

During those warm August days, our ragtag group forded swift rivers and ascended steep hills to view a range still shrouded in snow. The horses stepped over fallen logs, threaded through narrow forest passages, and broke out above treeline, where we were rewarded with a panorama that wouldn’t fit in my camera: rolling green hills against a layered backdrop of purple, gray, and white peaks. A stray caribou was startled by us and vice versa. On the other side of a deep draw, he paused to take us in, then blasted over the ridge without effort.

I remember one downhill ride that was so scary, I flashed on a scene in “Man from Snowy River.” My stirrups were touching my horse’s ears. That day, I felt like She-Ra the Conqueror when Pam Houston threw me a bone: “You have a natural seat,” she said. (Woo-hoo!) On another day, we skirted vast Braye Lake and dismounted at the far end to wade, watch the tundra swans, and nap. Was there another world beyond this one?

After the last ride and the group photos and the melancholy of a final dismount, Kris, Sherry and I took turns in the little sauna. The woodstove was crackling and the water heated quickly. I cleaned up from the inside out, sweating, shampooing, ladling cold and hot water for a sweet rinse. Afterward, we rested on the rocky bank of Beaver Creek, and dried our hair in the chill air of sundown.

“I have a natural seat,” I said to my mountain-woman friends. “Did Pam Houston tell you that you have a natural seat? No? Oh, too bad.”

Oh, yeah, I guess this beats “American Idol.”

CHRISTMAS IN NORTH POLE, ALASKA

© Sunday Oregonian, December 21, 2008

By Tricia Brown

Dear Santa, I sometimes don’t believe in you, but now I’ve changed my mind. I believe in you, now, and if I get these toys for Christmas I’ll be the most believing kid in the world.

Yes, Santa, we still believe.

We believe because we’ve found the place where Christmas lives year-round. Where reindeer are sheltered next to a rambling, white-and-red house cloaked in snow at –20F. Where street signs read Mistletoe Drive, Santa Claus Lane and Holiday Road.

This is North Pole, Alaska, an incorporated, home-rule city of 2,000, just a dozen miles southwest of Fairbanks. From the highway, you can see the landmark 43-foot fiberglass Santa weighing 900 pounds and measuring 33 feet at the waist. Now that’s a lot of Santa. But around here, there’s always a lot of Santa. Lampposts shaped like candy canes. Dinner at The Elf’s Den. Going to school on Snowman Lane. Then there’s Santa’s Flowers, Santa’s Fur Factory, Santa’s Travel World, Santa’s Motorsports, Santa’s Plumbing & Heating Wholesale and Santa’s Pull Tabs. Lotsa Santa.

Dear Santa, We hope you and your reindeers got home safely. We liked the presents very much. Lachie and I will try to keep our rooms tidy. I will work hard in school this year. Love from Lachie and Claire in Australia.

We believe, because the most famous address in town is 101 St. Nicholas Drive: Santa Claus House, where it’s been Christmas everyday since its founding in 1952. Inside, the jolly old elf receives guests with the first lady of Christmas from Memorial Day to Labor Day, and all through November and December. Throughout the crowded rooms, toys and Christmas collectibles jam shelves from floor to ceiling, greenery boughs are wrapped in twinkling lights, and evergreens are laden with ornaments. There’s a lingering aroma of cookies and hot chocolate.

Children entering the double doors immediately cut their eyes left to the throne room—Is he there? Reactions vary from bug-eyed, over-the-top joy, to abject fear and crawling up Daddy, to something in between. Santa’s used to it. He reads their signals like the professional he is. He gets their letters. That’s a real beard.

Next door, half of the famous reindeer team—Dasher, Blitzen, Comet and Cupid—roam in a spacious pen between Santa Claus House and Santaland RV Park. This month, you’ll find ice sculptures, not campers, throughout the park for the “Christmas in Ice” invitational ice-carving contest. Fantastic ice figures, real and abstract, are lit with colored spotlights in the mid-afternoon twilight. Families are bundled up so warmly that parents barely recognize their own young. And for these kids: a playground entirely made of ice. After a while, they shuffle next door, peel off layers, blow their noses, and nest on Santa’s lap for a chat.

Dear Mr and Mrs Clause. I am sending this letter because I thought you weren’t real but I guess you are real since you sent that letter through the mail. I was really freaked out because I thought you were a story because I caught my parents bringing in presents that said, “From Santa Clause.” But since you are real I should give you a list of what I want for X-Mis . . .

We believe, even though this isn’t the geographic North Pole. At latitude 64° 45′ north, the average temperature is –15F in December, although locals know it can drop down to –30 or –40 and hang there for weeks. Sixty below or worse? It happens.

Those kinds of temperatures are hard to explain, beyond “Yes, but it’s a dry cold.” So the people describe what it does to inanimate objects, leaving room to imagine what it would do to you. Heating oil gets thick; a cup of boiling water, flung into –30 air, vaporizes; plastic, like that faux leather boot at the base of your stick shift, shatters like glass.

And yet, the hardy children of North Pole go outside for recess down to –20. It’s not a problem if they’re dressed properly, so even on weekends, Moms tell their kids: Go play while it’s light!

Today, on winter solstice, the sun will rise above the horizon for a mere 3 hours and 42 minutes. On the flip side, June 21, the town is sun-kissed for 21 hours and 49 minutes. Summers usher in 80-degree days and tourists trail in and out of Santa Claus House by the thousands. There are mosquitoes, too, by the thousands. Hard to imagine that in December. But now, when the trees are flocked with real snow and soft-green northern lights are whispering across the sky, it’s hard to care about June.

Dear, santa Thankyou for the letter and the pictuer.i will lay out you some cookies and milk and carots and water for the rian deers.all i need to know is how many rain deers you have?

Still we believe. In 1949, Con and Nellie Miller came to Alaska’s Interior, just about broke, and began a fur-buying venture. Con flew into area Athabascan villages to do business, often wearing a Santa suit to entertain the kids. A few years later, the couple was constructing a trading post outside Fairbanks, when a boy greeted Con with, “Hello, Santa! Are you building a new house?” That nailed the name for the new store.

In 1953, Con traveled to Juneau to see the territorial governor, hand-carrying incorporation papers for the new City of North Pole. He would serve as its mayor for a record 19 years. Meanwhile, Nellie stayed busy as Marriage Commissioner, joining thousands of couples right there at Santa Claus House. The couple raised two boys, Terry and Mike, each of whom achieved the office of Alaska Senate President, and a daughter with a memorable name, Merry Christmas Miller. Over the years, Con and Nellie were beloved by all as Santa and Mrs. Claus.

“I believed in Santa probably longer than most kids did,” says their 57-year-old boy, Mike. “Actually, I even watched him dress sometimes, becoming Santa. But at some point, he changed from being my Dad to being Santa.”

Mike married his coworker and sweetheart, Susan, on Dec. 27, 1974, a day when temps dropped to –45 in North Pole. “I always wanted a Christmas wedding,” says Susan.

Nowadays, the second and third generation of Millers run the retail business, the website and the Letters from Santa mailings, take care of reindeer, and operate the RV park. Last summer, they opened a second store in Ketchikan, Alaska, to capture some of the cruise-ship passenger dollars.

But after Con’s death in 1996, finding another Santa to match his devotion was hard. For a while, they worked with local stand-ins before turning to an agency. The family demands an extensive interview process to get the right man with the right heart.

“Most of our Santas have been mall Santas,” says Susan. “They’ve had to run those kids through. And they’d get the eye if the kids were on their lap too long. Here, there’s a lot of one-on-one time. In summer, sometimes he’ll be on the cell phone talking to somebody’s family, saying, ‘Yes, they’re really at the North Pole.’”

Each year during countdown to Christmas, the media comes calling—in person or on the phone—including nationwide radio stations seeking a sound bite. NBC’s Today Show faithfully sends an underdressed reporter to point at a thermometer, proving how very, very cold it is at North Pole.

“It’s funny, some of the reporters they bring up are out of L.A.,” Mike says sympathetically.

When Mike’s mother, Nellie, died three months ago, newspapers across the country carried the story, some a bit more calloused than others, such as the headline that read, “Mrs. Claus Dead at 92.”

Dear Santa, thank you for sending me a letter. Now I have a question for you when you said I was almost at the top of your list did you mean good or bad list?

We believe because Santa writes letters. For 20 years, the North Pole post office was located in Santa Claus House. Since 1952, they’ve been mailing personalized letters from Santa; in the early 1960s, they added deeds to one square inch of North Pole.

“In the beginning I remember my Dad used to hand-write the letters,” says Mike, “and he just couldn’t keep up with it. Now people can get online and personalize the letters right on our website.”

Each December, hundreds of thousands of letters arrive at the North Pole Post Office, a mega-complex in comparison to the community’s size. Volunteers help with sorting and processing, running the cancellation machine, and answering some letters that could break the hardest heart. Kids aren’t always asking for toys. Sometimes they want Santa to fix things, like bring a Dad home from Iraq, or make an old dog a puppy again. Or just to say “Dear Santa, I like Rewdolphin the best, but don’t tell the other reindeer. They might get jealous.”

Growing up the son of Santa and Mrs. Claus, Mike Miller believes in protecting innocence: “It’s nice to hold onto that as long as you can. Like our nine-year-old granddaughter . . . third-graders do a lot of talking, but she is still holding out that there is a Santa.”

He continues to make glad the heart of childhood.

And others who’ll simply believe.

AN ECO-TREK CONNECTS FIVE SISTERS-AREA LODGES

© Sunday Oregonian, November 9, 2008

By Tricia Brown

Normally you wouldn’t dream of coupling the words “hiking” and “luxury accommodations.” A day on the trail might conclude at a dusty, oven-baked car, or maybe at a campsite, where you fire up the single-burner camp stove. Rehydrated Beef Stroganoff, anyone? Perhaps some delectable gorp?

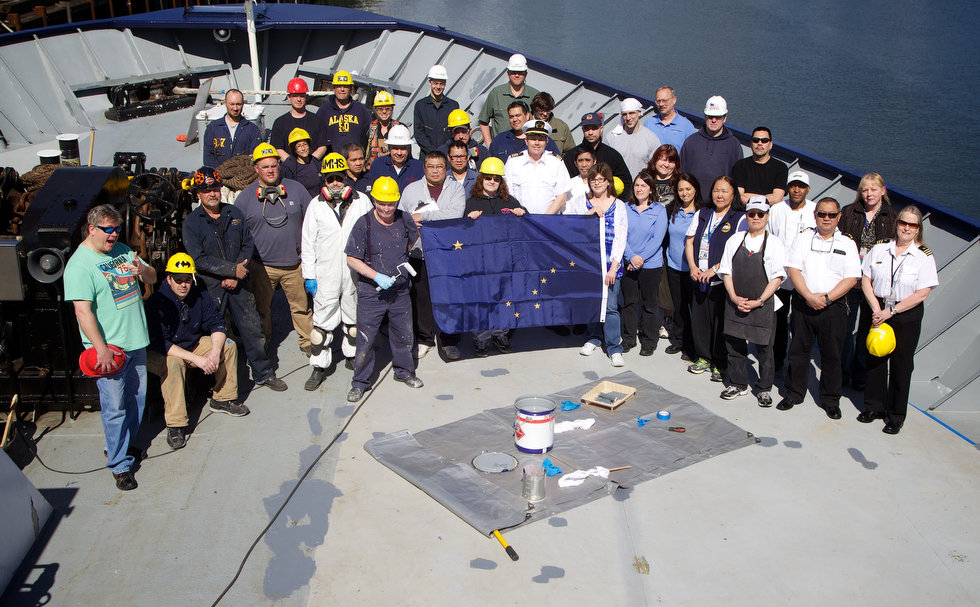

Alaska’s MV Malaspina: Getting Ready for Act II

By Tricia Brown

Special to the Oregonian, 2013

Deep in the heart of Swan Island’s industrial sprawl, a rebirth is taking place at Portland’s Vigor Shipyard. The first of the Alaska Marine Highway System’s original ferries, the MV Malaspina, is preparing for her 50th birthday with an $8 million makeover.

We’re talking more just fresh paint. From electronics to mechanics to murals and flooring, she’s getting a thorough overhaul/refinish while retaining that vintage look of Jan. 21, 1963, when she sailed north from Seattle’s Lockheed Shipyard on her maiden voyage.

On April 2, the inside was a glorious mess with reconditioned floors covered by plastic, “Wet Paint” signs tacked near doorways, and piles of life jackets filling the fore observation lounge with an orange glow. Overhead on the smokestack, a fresh design in gold paint was a flashback to its first decade. Ten days later, the crew moved out of their Portland hotel rooms and onto the boat.

The plan: leave Portland on April 25 to set sail on what AMHS is calling “The Golden Voyage.” From May 1-5, cultural events and shipboard open houses are planned in Ketchikan, Wrangell, Petersburg, Juneau, Haines and Skagway. Included are two rare day trips—to Misty Fjords National Monument and to Tracy Arm Fjord.

The romance and adventure of ferry cruising along Alaska’s coastal waterways is all you’ve imagined. It’s a time to power down, to read and play cards, snack and fix your eyes on the beauty outside the windows. Oregonians know rain and green. The Inside Passage is that and more, especially when the sun spills onto the dazzling high places alongside the unending waterways. From the comfortable seating in the observation lounge, rain may bead the windows, or the quiet water may reflect hulking mountains. Either way, you can’t stop watching the slow-moving pictures around you—this is the largest contiguous rain forest in the world, the Tongass National Forest. Peace settles in like an old friend, and disembarking leads to adventure.

Taking the ferry north to Alaska begins with a road or rail trip to AMHS’s southernmost terminal in Bellingham, Wash., where the mainline ferry Columbia begins and ends each round-trip. Passengers seeking a direct route to Haines to connect with the mainland highway system will spend a weekend on the water. The Columbia leaves Bellingham each Friday at 6 p.m. and arrives in Haines on Mondays about noon, with brief stops at Ketchikan, Wrangell, Petersburg and Juneau. In port, watching people driving on and off the ferry is more entertaining than any reading material, by the way.

Larger, high-speed ferries such as the LeConte and Kennicott take on the cross-gulf excursions to Southcentral Alaska, covering the big water that would cause smaller ships like the Malaspina to roll sickeningly.

Costs vary, depending on your demand for creature comforts. A walk-on traveler bearing a backpack with pup tent, sleeping bag and cheap eats can get from Bellingham to Ketchikan for $239—a 38-hour running time. If she decides to bring along her bicycle, it’s $38 more; a Subaru, $515 more. And if she wants to pop for a two-berth room with a view, another $257. You can build your personalized itinerary on the AMHS website.

Of late, the Malaspina has been a day boat, moving people and vehicles between Skagway, Haines and Juneau. And this summer, she will return to that route, until Fri., Sept. 6, when the Malaspina will take over the Bellingham-Skagway run while the Columbia is out for a tune-up.

Once she was the toast of the fleet, the first of its kind, constructed for $4 million and designed by renowned marine architect Philip F. Spaulding, who also would draw the plans for seven other Alaska Marine Highway System (AMHS) ferries, with still more for BC Ferries, Washington State, and other clients.

Gliding toward Ketchikan on Jan. 23, 1963, the new ship inspired cheers and flag-waving from a crowd numbering in the thousands—nearly half the town. Alaska Gov. Bill Egan and other VIPs, onboard for the maiden voyage from Seattle, waved from the rails on a day of great speech-making. But it wasn’t the governor who had turned out the townsfolk of Ketchikan. It was the lovely blue-and-gold ferry itself, painted in the bold colors of their new state flag. The Blue Canoe. And what she represented: freedom.

“What a beautiful, uplifting sight that was,” remembers Betty J. Marksheffel, who witnessed the ship’s arrival. “We could take our car, or walk onboard, and go somewhere!”

The coastal town on Revillagigedo Island was then home to about 6,500 people. They hadn’t seen a mainline passenger ship in their port since 1954, when the Alaska Steamship Co. ceased its sailings. In those nearly 10 years, the people of Ketchikan and other small communities tucked along the Inside Passage had learned the definition of isolation.

For Ketchikan, the nearest connection to a mainland road was 90 miles south at Prince Rupert, B.C. To the north 235 miles was the capital, Juneau, also disconnected from the road system. This development was huge. This was a highway on the water. For the first time, the towns south of Juneau were linked with regularly scheduled passenger and vehicle service. Mainland road access at Prince Rupert and Haines meant there was a way out.

At its christening, the Malaspina was a spacious 352 feet long, with a 74-foot beam, able to carry 500 passengers, 50 crew, and more than 100 vehicles. There were 54 four-berth staterooms and 29 two-bunk cabins, hot food, a cocktail lounge and bar, business lounges, movie theater, gift shop and showers. You could board with a car, truck, camper, bicycle, motorcycle, even your kayak. To the Alaskans, it was mind-boggling.

By June 1963, the “Mal” was joined by the MV Taku and MV Matanuska. In those early days, the three workhorses would comprise the mainline fleet between Prince Rupert, B.C., and Skagway. In its first year the AMHS served 83,000 passengers and 16,000 vehicles.

In 50 years hence, the ferry system has expanded to cover 3,500 nautical miles from the Washington state terminal to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands. The fleet includes ocean-going mainline vessels, day boats and vehicle ferries. In all, some 11 vessels serve 35 communities. In 2011, state ferries carried nearly 335,000 passengers and more than 114,000 vehicles. Meanwhile, $150 million was recently appropriated to get a new class of ferries off the drawing board and into the water: the Alaska Class, which will lack state rooms and other amenities, but will offer streamlined passenger service between smaller ports.

Over the years, those three original ships somehow managed to avoid retirement, even as the fleet grew, and newer, faster ferries came online. In 1972, the Malaspina sailed to Portland for refitting and lengthening to 408 feet at Willamette Iron and Steel. For the state, the move was less expensive than ordering a new ship. Still, in the 1990s, the Mal and its sister ships were seen as approaching “the end of their useful lives.”

And yet, in 2013, this vintage beauty has proven them wrong—still offering sweet freedom to travelers as she has for 50 years—ready for Act II.

For information on special sailings, community events, schedules and pricing, consult the Alaska Marine Highway System website at www.dot.state.ak.us/amhs/. On their Facebook page, you’ll find itinerary ideas, photos old and new, and traveler feedback.

Off the Watery Path

Unlike the cruise-ship passengers with their tight schedules, ferry travelers can take their time. AMHS allows you to step off where you’d like and pick up another ferry later. However, reservations are recommended, especially if you’re traveling with a vehicle. Browse town websites for community events, special museum exhibits or festivals, Native cultural celebrations, and stay in port an extra day or two. So plan, plan, plan, but leave some dead air in your schedule for spontaneous decisions, and don’t be afraid to ask the locals for recommendations. Every community has its own personality. Tap into it.

Ketchikan: Long known as Alaska’s Gateway City, this has been the first port of call since the early days of tourism. Explore the famous Creek Street district, with shops on stilts over the water’s edge. But also get up north to Totem Bight State Historical Park or stop by Saxman Totem Park. Each is a cultural treasure showcasing the carving skills of Tlingit and Haida carvers, from antiquity to the present. Go hiking or take a ride on a zipline. From here, take another ferry to outlying villages for a real taste of Alaska life. www.ketchikanalaska.com

Wrangell: The Tribal House on Chief Shakes Island was restored and will be rededicated during the Malapina’s Golden Voyage. This community is known for some amazing petroglyphs—check at the museum for details. On a hike to Rainbow Falls, you can pick berries. At Anan Observatory, watch bears feeding on salmon headed up the Stikine River. www.wrangellalaska.org

Petersburg: A classic fishing village settled by Scandinavians in the last century. Its annual Little Norway Festival is held in mid-May. Fish off the dock or hire a charter; go whale watching; hiking; book a flight to LeConte Glacier. www.petersburg.org

Sitka: This was once Russian Alaska’s capital city, then known as New Archangel. Its history is steeped in Russian influence. From June 7 to July 5, the city hosts its annual Summer Music Festival with classical musicians from around the world. Bike tours and rentals are available, or go diving. www.sitka.org

Juneau: Alaska’s state capital built on a Gold Rush heritage. Adventuresome travelers can go glacier hiking or even dog-sledding on Mendenhall Glacier. Take the Mount Roberts Tramway for photo-worthy pictures as you ascend the mountain. The Alaska State Museum is a worthwhile stop. Wings Airways offer a flight over the icefield to the historic Taku Glacier Lodge with a memorable salmon dinner included. www.traveljuneau.com

Haines: From the water, this is one of the ferry line’s prettiest towns, set against a backdrop of stunning mountains. This is the home of a once-bustling Army post, Fort Seward, and many of the historic buildings are still standing. Learn more at the local museum. Each fall, thousands of bald eagles arrive to feast on a late salmon run in the nearby Chilkat River. Lots of bear activity, too. The road out of town lands you in Canada for a few hours before crossing back into mainland Alaska. www.haines.ak.us

Skagway: The honky-tonk world of the Gold Rush is alive in Skagway’s false-front buildings and narrow-gauge railway. The White Pass & Yukon Route offers a great day trip along the path taken by many stampeders headed for the Klondike. Zipliners will love this town. Go see Jewell Gardens for their wondrous blooms and glass-blowing demonstrations. The trailhead for the infamous Chilkoot Pass is up the road in Dyea. RVers can pull off the ferry here and take the Klondike Highway to the Alaska Highway in Whitehorse, Yukon. www.skagway.com

Tips for the Wise Planner

- Alaska’s ferry system has been called “the poor man’s cruise ship.” Take that as a compliment. If you are on a baseline budget and quick-footed, you will find deck space for your tent, or you may claim a reclining chair in the fresh air (but out of the rain) for you and your sleeping bag. The clever traveler can locate a good solarium spot beneath overhead heaters on those particularly chilly days. The cafeteria serves salads, fruit, hot sandwiches and gallons of coffee, and finer dining is available, but to save, it’s absolutely okay to bring your ice chest and thermos. Pay for your showers. Enjoy your book in the lounge. And relish the same magnificent views as those folks in the four-berth stateroom with amenities.

- Ask yourself, “Do I want to do this twice, coming and going?” If it’s no, decide whether to fly up and ferry back, or vice versa. Also you may choose to board in Bellingham, or shave off a day and fly to Ketchikan to start your voyage. That’ll give you some extra time to explore Alaska’s Gateway City, too, just as you could if you started in Skagway and cruised south. Discounts are available for mirror-image itineraries.

- Alaska Airlines has the only commercial airliner service to Ketchikan, with three flights a day from Seattle. To get to or from the airport, you must board a small ferry between the airport on Gravina Island and Ketchikan on Revillagigedo Island. Heading out, travelers shield themselves against (sometimes) forceful wind and (more often) pelting rain to line up for the walk-on ferry ride. Once upon a time, Ketchikan asked the state to build a bridge to their airport. Remember the proposed “Bridge to Nowhere” that garnered such national ridicule in 2005? It really was from one place to another…and this was the place. After so much uproar, the approved funding was ultimately channeled elsewhere.

- Finally, remember that the Alaska State Ferry line isn’t limited to the Southeast Panhandle. Connecting to the Southcentral and the Aleutian Chain lines is as easy as switching trains elsewhere. So include Cordova, Valdez, Homer, Seldovia, Kodiak, and the Aleutians in your dream itinerary.